Mention  canal cruising in southern France and most people think of the Canal du Midi, from the Etang de

Thau to Toulouse. Its 150 miles of lovely scenery make the Midi one of the most popular routes in Europe.

canal cruising in southern France and most people think of the Canal du Midi, from the Etang de

Thau to Toulouse. Its 150 miles of lovely scenery make the Midi one of the most popular routes in Europe.

But as someone once said about a too fashionable restaurant, "Nobody goes there any more, it’s too crowded." The crowding of the Canal du Midi is making it a victim of its own success. It’s also in ecological trouble: the 40,000 plane trees that line its banks are fast becoming diseased and many are likely to be felled in the coming years.

So it’s probably no surprise that people are starting to discover the other end of the classic Canal des Deux Mers, the Canal Lateral de la Garonne runs from Toulouse westward towards Bordeaux, following the River Garonne. It shares many of the characteristics of the Canal du Midi, but is more peaceful, quieter and more relaxing... and much overlooked.

THE NARROWBOAT OPTION

I took the opportunity to take an English style canal boat along this little-trafficked waterway and was charmed by what I saw. We were the guests of the Meilhan-sur-Garonne division of Minervois Cruisers, a small hire boat company owned by the Warwickshire-based Napton Narrowboats hire fleet. Minervois Cruisers started on the Canal Midi at Le Somail, with a fleet of British-built narrow and wide-beam boats. A couple of years ago the fleet split, basing four boats at Meilhan-sur-Garonne.

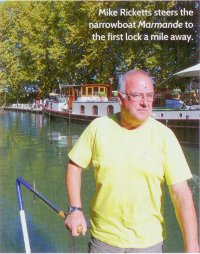

As an experienced narrowboater, I knew more or less what to expect from our boat, Marmande. But many people used to the white pénichettes that are the more conventional French cruiser fare might ask: Why a narrowboat in France? Granted, the steel hull is sturdy, but why sacrifice space? One answer, says Minervois Cruisers manager Mike Ricketts, is that the narrowboat format remains extremely popular with British holidaymakers, Many are boat-owners, considering bringing their own boats to France, and interested in trying out the narrowboat format on French waters and seeing if it suits.

Having seen inside a couple of pénichettes during our week, I can vouch

that even on the roomy French canals the narrowboat remains a supremely practical format -

although you might chafe at the narrow single beds if you are used to double.

Having seen inside a couple of pénichettes during our week, I can vouch

that even on the roomy French canals the narrowboat remains a supremely practical format -

although you might chafe at the narrow single beds if you are used to double.

SETTING OFF

We had decided in advance to travel to Agen and back for the week, sticking to the canal. In theory you could spice up your week by dropping down to the River Baise halfway along the route at Buzet. I had heard that the towns on the Baise can be more interesting, but the predictability of the canal appealed - plus the level of industrial heritage and the certainty of reaching Agen, a city I had wanted to see.

We set off mid-morning after the mists had evaporated, with Mike showing us how to operate

the locks. These come slowly, but often enough to punctuate the tedium of long straight stretches.

We set off mid-morning after the mists had evaporated, with Mike showing us how to operate

the locks. These come slowly, but often enough to punctuate the tedium of long straight stretches.

For English boaters used to the hard mechanical workings of English locks, operating those on the Garonne really couldn’t be simpler, even though there are no lock-keepers. A hundred metres or so before you reach each lock, a yellow hose dangles from a suspended wire across the canal; you grasp the hose as you go past and give it a quick turn. This alerts the mechanism and sets everything in train. The lock empties or fills, and opens. You then just cruise in and steady the boat on the ropes; whoever has lockside duty presses a button to complete the locking process. The simple traffic-light system - alerting you if the lock is already busy or if the automatic system has noted your presence - is also easy to follow.

Given this, why are there strict lock opening hours? Locking only starts at 9am, and ceases at 6pm, earlier in winter. Perhaps it was because we were warned that occasionally these automated locks would malfunction, and we’d need to call for help. After a trouble-free first day this indeed proved the case, and almost every day thereafter, we had to press the button that telephoned the local Voies Navigables de France (VNF) office, and speak into the microphone. As someone with only limited French I feared it would be a tricky process, not least because during the week I didn’t meet a single VNF official who spoke English.

However, all I needed to do was state the name of the écluse (lock) and say

"problème", and after (at most) ten minutes, a little

white VNF van would trundle up. The blue uniformed technician would silently open a

cabinet, reset a switch and make a note on a clipboard, depart with a wave, and everything

would resume. I was told that the problem is worse in the autumn, since many of the glitches are

due to plane tree foliage jamming the sensors in the locks.

However, all I needed to do was state the name of the écluse (lock) and say

"problème", and after (at most) ten minutes, a little

white VNF van would trundle up. The blue uniformed technician would silently open a

cabinet, reset a switch and make a note on a clipboard, depart with a wave, and everything

would resume. I was told that the problem is worse in the autumn, since many of the glitches are

due to plane tree foliage jamming the sensors in the locks.

CANALSIDE CHARACTER

This aside, immediate impressions of this canal were overwhelmingly positive. Firstly, there

is the simply glorious array of plane trees that border the canal for long stretches.

In places they look ravishing. They rival - or even outshine - those on the Canal du Midi,

and in many cases look better maintained. They are arranged in two rows on each side, and serve

to both strengthen the canal banks and to provide shade in the hot southern sun - something that

must have been more important when travelling this waterway was hard manual work.

This aside, immediate impressions of this canal were overwhelmingly positive. Firstly, there

is the simply glorious array of plane trees that border the canal for long stretches.

In places they look ravishing. They rival - or even outshine - those on the Canal du Midi,

and in many cases look better maintained. They are arranged in two rows on each side, and serve

to both strengthen the canal banks and to provide shade in the hot southern sun - something that

must have been more important when travelling this waterway was hard manual work.

The second glory is the superb towpath, which is immaculately maintained along the entire length of the canal's 110 miles. The result of an EU funding exercise a few years ago, the route now attracts cyclists like flies, and on a fine day it’s a rare moment when there’s not at least one cyclist in sight.

Near Fourques, a stone memorial records the explosion, in 1908, of the petroleum barge Le Gascon, which killed five boatmen. Like the barge itself, little now remains of the story, save this lonely weathered stone.

On our first night we stopped at Villeton, where we first encountered something we soon found is common on this canal: the expatriate British boat-owner who has fled the hire-boat crowds of the rest of France for a little peace and quiet.

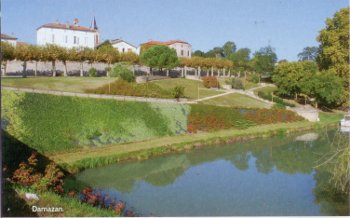

A few miles further on, the lovely old fortified town of Damazan looms over the canal. While in many respects a fairly typical mediaeval fortified town, it has a lovely market square surrounding the local elevated mairie. I was particularly struck by the avenue of elegant espaliered plane trees that accompanied us as we walked up the hill from the town's halte nautique. For British visitors, Damazan has one extra claim to fame: a thriving cricket club, one of the very few in Southern France, which serves as a weekly pilgrimage for cricket mad expatriates. "Matches start at 1pm, tea is served at 3.30pm and the match is usually over by 6.30pm," says the club guide optimistically.

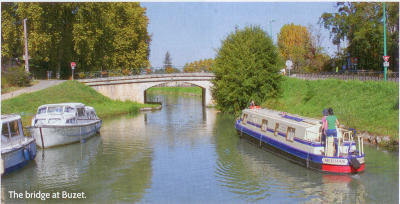

Nearby Buzet is a key junction on the canal; here, a staircase lock links it with the rivers Baise and Garonne, which link further with the Lot. At Buzet you must decide: descend to the river, or continue in the security of the canal.

There's a lot to be said for venturing onto the river, and especially the lovely Lot, and the Baise, with numerous communities embracing it. Nevertheless, the canal was built to ensure predictable transport, and we chose to stay on the canal and head for Agen.

THE AMAZON

Once past Buzet, the waterway enters a 'lost' section, which my companions called 'the Amazon'. Here, no longer lined by elegant plane trees, scrub and bushes hang over the water until the main channel is crowded in to barely the width of two boats, and you half-expect to see dugouts emerging from behind the bushes. A close pair of locks negotiated, the canal has now risen enough to spring you on an elegant aqueduct over the River Baise, which has turned south.

Emerging from the jungle, the canal passes neat orchard fields until you soon emerge at

Serignac. This unassuming and sleepy town has an unusual twisted church spire that itches to

be photographed, and I did it twice - once in daylight, once while it was floodlit.

Emerging from the jungle, the canal passes neat orchard fields until you soon emerge at

Serignac. This unassuming and sleepy town has an unusual twisted church spire that itches to

be photographed, and I did it twice - once in daylight, once while it was floodlit.

The moorings at Serignac are extremely popular during the summer, particularly with liveaboard barges. This is not least because the local mairie offers free mains electricity on shorelines. One barge owner admitted to staying for several weeks on the mooring!

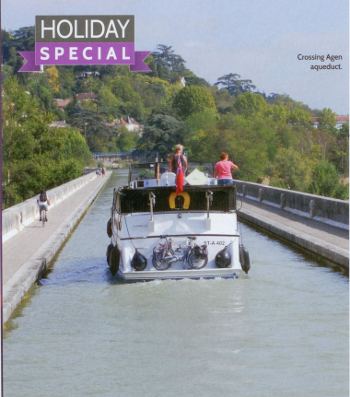

After Serignac we once again entered the wild 'Amazon' territory, until a sharp turn left brought us to the bottom of the flight of four locks that - over a distance of barely a kilometre - lift the waterway to the canal's showpiece, the magnificent Agen aqueduct.

This structure, some 600 yards long and borne on 23 arches, opened in 1843. It is still the second biggest in France, and a national monument. It is there to take the canal across the River Garonne, the first time boaters will have seen the river since Buzet. A glance down to the river tells you why the canal was built in the first place. By the time the Garonne has reached Agen, although still extremely wide, it has become shallow and treacherous.

AGEN AND BACK

The aqueduct serves as an impressive 'gateway' to the city, and immediately the atmosphere changes. Those who yearn for nightlife will enjoy the easy access to world culture.

As a tourist destination Agen’s PR effort is two-pronged: the plentiful plum orchards in the area have made it the world capital of prunes, and locals seem to have made rugby their secular religion. Everything in the souvenir shops seems plum-coloured and rugby ball shaped. Yet the city is far more than that, and could easily repay a week’s stay with different activities every day.

Sadly, we had to make the return journey after barely 24 hours. While it’s possible to hire some boats on one-way trips, a return voyage does allow you to revisit places that catch your eye. For us, a further stay in Damazan brought out some of its best features. There were also memorable stops in Le Mas d’Agenais, to see the original ‘Rembrandt’ crucifixion altar piece in the local church, and the chateau of the Comte Marcellus, said to be crucial to the rediscovery of the Venus de Milo in 1820. Particularly haunting were the many war memorials, particularly those of World War II. Unlike those in Britain, they bear testimony to the many resistance fighters and pure civilians who were either shot - or deported.

I returned the boat with a sense of sadness that we hadn’t been able to examine so many other things that had caught my eye along the way. But as those familiar with English narrowboats will know, there is nothing quite like the sense of things catching your eye fleetingly as you potter along at a modest speed, and of having the tiller in your hand. The fact that it’s complicated to stop, that you have to keep going, actually makes you look more longingly at things.